Textbook Wars — The Missing Lessons of the Vietnam War

April 29th is the 47th anniversary of the end of what is known in America as the Vietnam War. As reported on page one of the April 30, 1975, New York Times:

The United States ended two decades of military involvement in Vietnam today with the evacuation of about 1,000 Americans from Saigon as well as more than 5,500 South Vietnamese. The emergency helicopter evacuation was ordered last night by President Ford after the Saigon airport was closed because of Communist rocket and artillery fire. The 1,000 Americans were the last contingent of a force that once numbered more than 500,000.

Vietnamese-American author Viet Thanh Nguyen ruefully observed in "Nothing Ever Dies, Vietnam and the Memory of War," his "searching exploration of a conflict that lives on in the collective memory of both the Americans and the Vietnamese,"

“All wars are fought twice, the first time on the battlefield, the second time in memory,” [1]

In 1968, rock artist Jimi Hendrix (a former U.S. Army paratrooper whose musical career coincided with the peak years of the Vietnam War) released his third album, a sprawling double album entitled “Electric Ladyland.” [2] The first line in the opening stanza of the recording’s longest track, 1983… (A Merman I Should Turn to Be), contains the following lyric, which foreshadows Nguyen’s insight:

Hooray, I awake from yesterday, alive but the war is here to stay…

Anyone who doubts if the Vietnam War is still with us should watch the September 13, 2021, meeting of the Tuckahoe Village Board beginning at the 1:47 mark. [3] During the meeting, which concerned a contentious series of Facebook posts by a local retail merchant and allegations that Tuckahoe officials orchestrated a boycott of the store at the urging of community members offended by the posts, the merchant and Mayor Omayra Andino (Tuckahoe’s first female and person of color to be elected to the position) engaged in a heated debate about the meaning of one post that appeared (albeit, confusedly if not incoherently) to doubt the patriotism of the American soldiers who fought in Vietnam by comparing them to the untrustworthy Capitol Police who let insurrectionists inside the U.S. Capitol on January 6, 2021. [4] The Mayor informed the audience that her father had served in Vietnam. She then attempted to explain how a post like this could be offensive.

Confusion about the Vietnam War is not surprising. [5] Decades after America’s involvement ended, no historical consensus has been reached as to what the Vietnam War was about. Even though North Vietnam released all American prisoners of war in 1973, nearly a half-century ago, flagpoles in Ardsley fly a flag depicting a silhouetted soldier held in captivity that was created in 1972 by The National League of Families of American Prisoners and Missing in Southeast Asia even though the official position of the US Government is that no American remains captive in Southeast Asia. Currently, the meaning of the POW-MIA flag has been reinterpreted to demonstrate a continuing commitment to the goal of the fullest possible accounting of all personnel not yet returned to American soil.” However, with respect to prisoners of war, the flag perpetuates the false belief we are still living in the pre-1973 era.

Recently, the National League’s flag was hijacked by groups claiming the individuals arrested for their illegal actions at the U.S. Capitol building in Washington, D.C, on January 6, 2021, are “prisoners of war.”

The National Alliance of Families POW-MIA, a splinter group of the National League, which claims that Americans are still being kept captive as prisoners of war, has its own flag, which is shown below:

Regrettably, this appears to be consistent with the larger truth that public understanding of the Vietnam War is a haven of “alternative facts.” [6]

During the January 6, 2021, attack on the U.S. Capitol, the flag of the Republic of (South) Vietnam (yellow with three red stripes), a political entity that ceased to exist in 1975, was displayed, providing another example of the haunting nature of America's military engagement in Vietnam. [7]

* * * * *

Professor Gerard J. De Groot observes astutely in his book "A Noble Cause? America and the Vietnam War”:

“The Vietnam debate is often like a balloon without a string. At issue are competing visions of America rather than conflicting explanations of the war.

One side sees a war of perpetrators and victims, the other of heroes and villains. The war was ugly, brutal, costly and riddled with perplexing moral contradictions. It did produce an extraordinary crop of casualties who still suffer the mental torment of combat and defeat. But it also saw men and women on both sides who served valiantly, acted morally and afterwards went home to lead normal lives.

It was fought in Saigon, Hanoi, Washington, Moscow, Beijing, Berkeley and Chicago, not to mention in towns and villages across America and in the tiny hamlets of South Vietnam. It was a war of guerillas, grunts and professional soldiers, protesters, politicians and ordinary civilians.”

Among the grunts was Kit Bowen of the First Infantry Division, A portion of a letter he wrote to his father in Oregon reflecting on his harrowing time in Vietnam is quoted in the last sentence of a paragraph appearing in American Pathways to the Present (the textbook used at Ardsley High School for its two-year course in American history) explaining the bewildering circumstances American soldiers found in Vietnam: [8]

American soldiers found the war confusing and disturbing. They were trying to defend the freedom of the South Vietnamese, but the people seemed indifferent to the Americans’ effort. The dishonest and inept government in Saigon may have caused that indifference.

As Bowen cynically explains in his letter:

“We are the unwilling working for the unqualified to do the unnecessary for the ungrateful.” [9]

In this Timepiece, especially in light of the ongoing political agitation about what is being taught in America’s K-12 schools (which now includes a spate of legislation barring the teaching of “Critical Race Theory,” or “divisive concepts) coupled with widespread efforts to ban certain books either from a school library or a curriculum as was done recently in Hastings), we will evaluate a variety of examples of how the history of the Vietnam War is presented in American Pathways.

Contemporary American involvement in Vietnam (or, more accurately, French Indo-China) can be traced back to the end of World War II. As the war ended, personnel from the Office of Strategic Services (the “OSS”), which was founded in 1942 as America’s first independent intelligence agency (and a precursor to the Central Intelligence Agency), were dispatched to Saigon in 1945 for a variety of purposes:

Repatriating American and allied prisoners of war (including American pilots who had been shot down on bombing raids over Japan);

Investigating alleged war crimes against prisoners of war held by the Japanese;

Gathering political and economic intelligence; and

Examining the condition of the American consulate in Saigon (down to the last piece of furniture) and determining the status of existing American commercial interests in Vietnam.

At the time, the headquarters for all OSS operations (under the command of the South East Asia Command, which Lord Mountbatten led) was in Kandy, British Ceylon (now Sri Lanka off the coast of India, which during World War II was governed by the British). In addition to Saigon, the OSS had detachments in New Delhi, Calcutta, Bangkok, and Rangoon. [10]

Once OSS’s post-World War II central mission to repatriate American prisoners of war ended, was there a need for any American military presence in Vietnam? In “Roots of Opposition, The Critical Response to U.S. Indochina Policy, 1945-1954,” Michael Gillen, Ph.D., explores the use in 1945 of American troopships, crewed by American seamen, to ferry back thousands of French troops back at the conclusion of World War II to Vietnam to assist them in re-establishing hegemony of their former colony (which had been occupied by the Japanese during World War II). As Gillen, a former Westchester resident and later a professor at Pace University and who briefly served in the merchant marine during the Vietnam War, meticulously explains, the use of American ships to carry French troops back to Vietnam gave rise to the first public protest against America’s Indochina policy. As Gillen details:

As members of the National Maritime Union, which distinguished itself as one of the more progressive American maritime labor organizations of the period, many of the Pachaug Victory’s crew members fully supported the cause of colonial peoples seeking to exercise self-determination. Not surprisingly, many of them reacted with indignation and anger at finding themselves being cast, in effect, as instruments of pro-colonial policy aboard ships carrying French troops to Indochina. Seamen aboard another ship, Winchester Victory, also found a means to protest the operation while still enroute to Vietnam. At a meeting held aboard ship on November 21 a report was presented by an elected committee regarding action already taken to protest the troopship movement. The committee reported that cablegrams had been sent to both President Truman and Senator Robert Wagner of New York, which read:

We, the unlicensed personel (sic) of the SS Winchester Victory, vigorously protest the use of this and other American vessels for carrying foreign combat troops to foreign soil for the purpose of engaging in hostilities to further the imperialist policies of foreign governments when there are American soldiers waiting to come home. Request immediate congressional investigation of this matter.

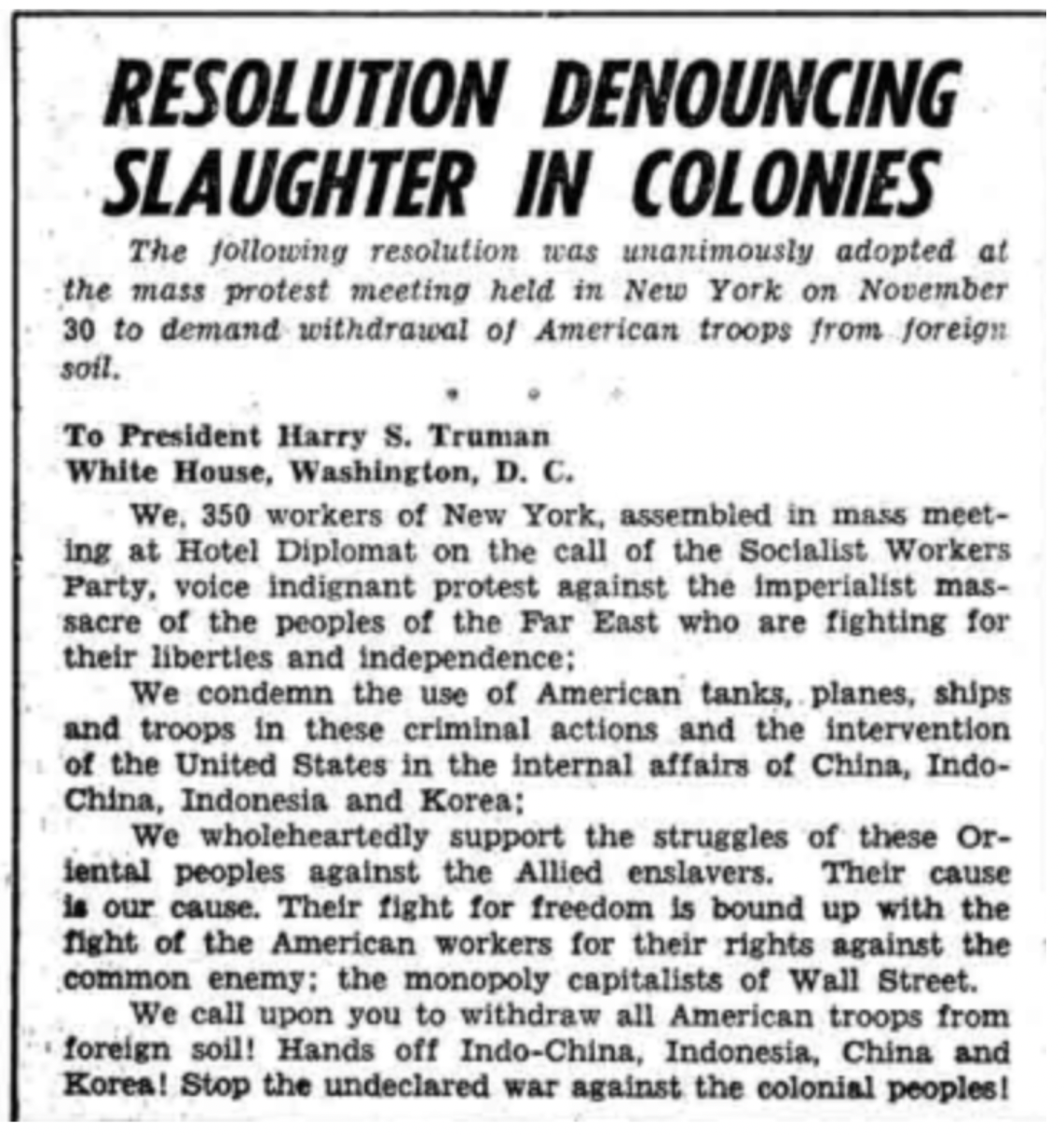

American seamen were not alone in opposing Washington’s abandonment of the principles of the Atlantic Charter, which opposed colonialism and recognized the rights of self-determination. [11] On November 30, 1945, as reported in The Militant (Published in the Interests of the Working People by the Socialist Workers Party), “despite bitter weather more than 350 people” participated in a rally held in the Hotel Diplomat in Manhattan supporting the independence movements of the colonial peoples in Indochina. [12]

* * * * *

With this broad background of the complex political situation in Vietnam that confronted America in 1945, let us look at the first main point presented in the Vietnam War part of the textbook, which states: [13]

The United States entered the Vietnam War to defeat Communist forces threatening South Vietnam.

Unfortunately, this claim is not only false; it was utilized as a ploy by American government leaders to justify the war for years. Specifically, the Pentagon Papers, the secret government history commissioned by the Secretary of Defense in 1967 to study the origins and developments of the Vietnam War, revealed that “ the government’s real reason for carrying on the war was not to assure the independence of an ally, South Vietnam, as the government had said over and over again, but the far more ambitious geopolitical aim – likely to take years and years to achieve -- of keeping China from expanding its influence in that part of Asia.” [14]

Subsequently,

“As the Pentagon Papers later showed, the Defense Department also revised its war aims: “70 percent to avoid a humiliating U.S. defeat … 20 percent to keep South Vietnam (and then adjacent) territory from Chinese hands, 10 percent to permit the people of South Vietnam to enjoy a better, freer way of life.” [15]

Surprisingly, for a textbook on American history, the dubious legality of the undeclared Vietnam War is not mentioned.. Instead, the text discusses the “Tonkin Gulf Resolution,” which was passed by Congress with a unanimous vote of 416-0 in the House of Representatives and 88-2 in the Senate in response to alleged attacks by North Vietnamese patrol boats on two navy ships, the U.S.S. Maddox and the U.S.S. C.Turner Joy in the Gulf of Tonkin while ostensibly in international waters in August 1964. The Resolution (which was treated like a Declaration of War), granted President Johnson the authority to use “all necessary measures to repel any armed attack against the forces of the United States and to prevent further aggression” by the communist government of North Vietnam.

In opposing the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, Oregon Senator Wayne Morse asserted, “the place to settle the controversy is not on the battlefield but around the conference table.” Ernest Gruening of Alaska, the only other Senator to vote against the Resolution, declared that “all Vietnam is not worth the life of a single American boy.” President Johnson reportedly described the Resolution like “grandma’s dress - it covers everything.” Pathways left out the part about “grandma’s dress.” The April 21, 1964, Congressional Record for the United States Senate (page 8604) contains this letter by Ardsley resident Lee H. Ball to Senator Gruening: [16]

However, not only had the resolution been written five months earlier by Johnson’s National Security Advisor McGeorge Bundy [17] (so it could be used to support Johnson’s plans for aggressive action against Vietnam if the right “Pearl Harbor” incident arose), but the military intelligence about the incidents at sea indicated that the first attack on August 2 was in response to covert operations by Americans against the Vietnamese (and thus not unprovoked) and that the second attack on August 4 never occurred. Pathways is strangely mute on these problematic facts other than admitting the evidence supporting the attacks was sketchy. The fateful Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, which was based on a lie, was the catalyst for the rapid escalation of American military engagement in Vietnam including the catastrophic deployment of significant numbers of ground troops in Vietnam.

H.R. McMaster, who briefly served as the National Security Advisor in the Trump administration, in his 1997 book “Dereliction of Duty: Johnson, McNamara, the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and the Lies that Led to Vietnam,” damningly claimed:

To enhance his chances for election, [Johnson] and McNamara deceived the American people and Congress about events and the nature of the American commitment in Vietnam. They used a questionable report of a North Vietnamese attack on American naval vessels to justify the president's policy to the electorate and to defuse Republican senator and presidential candidate Barry Goldwater's charges that Lyndon Johnson was irresolute and "soft" in the foreign policy arena.

Disillusioned by the lack of American military success in Vietnam,

McNamara argued in a 1967 memo to the president that more of the same — more troops, more bombing — would not win the war. In an about-face, he suggested that the United States declare victory and slowly withdraw. [18]

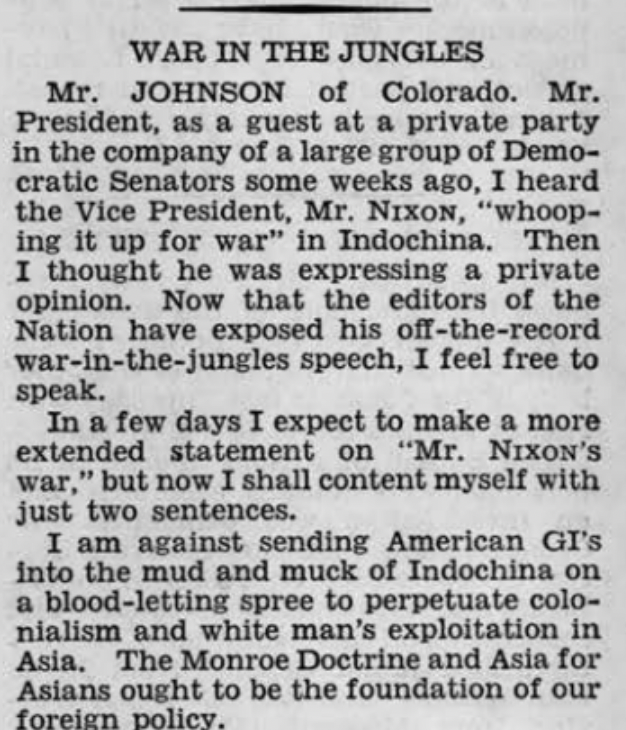

Puzzlingly, while John Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson were Senators, both opposed sending American ground troops to Vietnam. On April 19, 1954, a date when both Johnson and Kennedy were serving as Senators, Colorado Senator Edwin Johnson uttered these unheeded words about what American foreign policy should be regarding Indochina:

Again, outside of a few sections on dissent on college campuses and the tragedy at Kent State, no mention is made in Pathways of the long-standing (and generally mainstream) opposition to American military engagement in Vietnam. While Pathways includes the shocking picture of a Vietnamese Buddhist monk self-immolating himself on a Saigon street in protest of the policies of the South Vietnamese government the Americans were supporting, students are not told that eight Americans also burned themselves to death in protest against the Vietnam War. [19] Nor does Pathways address the war from the perspectives of the African-American or religious communities including the words delivered on April 4, 1967, by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. at the Riverside Church in Manhattan in a remarkable speech entitled “Beyond Vietnam - A Time to Break Silence,” given under the sponsorship of Clergy and Laymen Concerned About Vietnam:

“The world now demands a maturity of America that we are not able to achieve. It demands that we admit that we have been wrong from the beginning of our adventure in Vietnam, and that we have been detrimental to the life of her people.” [20]

Locally in Westchester, on September 2, 1970, fifteen years after Ho Chi Minh (who was rumored to have been assisted by OSS operatives in Hanoi serving under Archimedes Patti) [21] declared the independence of Vietnam from France in a proclamation paraphrasing the U.S. Declaration of Independence, the following appeared in the Herald Statesman illustrating the national schism in the nation over the Vietnam War, which had been rocked by the killing of four unarmed students at Kent State University by the Ohio National Guard on May 4, 1970. [22]

As Degroot recognized, the Vietnam War was inhabited by heroes and villains. One searing incident had both - the massacre at My Lai. Here is how Pathways describes it in a section that appears following a paragraph about communist atrocities in 1968 during the Tet Offensive: [23]

Surrounded by brutality and under extreme duress, American soldiers also sometimes committed atrocities. Such brutality came into sharp focus at My Lai, a small village in South Vietnam. [24]

At My Lai, under the orders of Second Lieutenant William Laws Calley, Jr., hundreds of Vietnamese women, children, and old men were rounded up. Pathways then quotes from Private Paul Meadlo about what happened next:

“We huddled them up, we made them squat down… I poured about four clips [about 68 shots] into the group. …. Well, we kept right on firing… I still dream about it….Some nights, I can’t even sleep. I just lay there thinking about it.” [25]

Pathways then flatly continues: “Probably more than 400 Vietnamese died in the My Lai massacre. Even more would have perished without the heroic efforts of a helicopter crew which stepped in to halt the slaughter.”

In an anodyne manner, the Pathways textbook describes how, upon realizing that a massacre was taking place, helicopter operator Hugh Thompson landed his craft between the civilians and the menacing American troops under platoon leader Calley's command and ordered his door gunner to shoot any American soldier who opened fire on the civilians. None of them did.

While the section concludes“in Hollywood style,” noting Calley’s conviction at trial (his life sentence was ultimately reduced, and he only served roughly three years in prison) and that three decades later, in 1998, Thompson and his crew received the Soldier’s Award (the highest award for bravery in a non-combat role) no mention is made of the extensive cover-up of the massacre at every level of the American command which was uncovered by an exhaustive investigation by General William Peers or that the killings at My Lai were part of several massacres that took place in Son My over three days (March 16-19, 1968). [26] Pathways ignores the complex contrast between two 24-year-old American soldiers who operated on the battlefield at Son My as if they were serving in separate armies. [27]

* * * * *

Criticism of how the Vietnam War is treated in American textbooks is not new. [28] Understandably, textbooks like Pathways, written by large committees of academics with varying degrees of expertise in different periods of American history, are subject to the rules of a national marketplace and, in some cases, the conservative political orientation of State Boards of Education like those in Texas which influence their content. Of course, almost every American history textbook has an ideological (if not mercantile) bias toward advancing a near-wartless view of America to its future citizens. In this regard, the Vietnam War is a tough sell. The reluctance to confront the reality that much that took place during the Vietnam War was a repudiation of American ideals is perhaps the reason why textbooks like Pathways focus on the personal experiences of soldiers and civilians during the war and downplay or avoid reflecting on the darker or even ghastly episodes of the nation’s history.

Concededly, any American textbook would struggle to explain the heinous actions of government officials who, despite knowing the war was a lost cause, continued to send soldiers to wage war in Vietnam, a war that John Kerry labeled as “one the soldiers tried to stop.” [29] Several commentators have observed that since Vietnam, America as a country has not been at war, only its military, due to the creation of an all volunteer armed forces. [30] Pathways also fails to provide an explanation for America’s military loss in Vietnam, which De Groot contends the root cause was that America backed an “ally that had no future in Vietnam.” Nearly twenty years later, a review of veteran British journalist and military historian Sir Max Hastings’ heralded 2018 book “Vietnam, An Epic Tragedy, 1945-1975” wrote that Hastings had reached a similar conclusion:

Although American forces often fought effectively on the battlefield, Hastings asserts, those successes proved irrelevant because Americans failed in the more important and far more delicate task of cultivating a South Vietnamese state capable of commanding the loyalty of its own people. It was as if the United States used “a flamethrower to weed a flower border. [31]

Finally, and inexplicably, Pathways, published in 2003 (and arguably in need of updating given the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan), fails to mention that in 1995, twenty years after all Saigon Embassy personnel were evacuated on April 29, 1975, the United States and Vietnam re-established diplomatic relations and have since enjoyed vast economic (e.g., trade, tourism, investment) and even military ties while cooperating on the devastating medical and environmental impact on Vietnam (and Cambodia and Laos) from the large-scale spraying of toxic herbicides (estimated at 19 million gallons) o defoliate the countryside during the war to deprive the “enemy” of food and a place to hide. Wars, unlike chapters in a book, rarely end. [32] So, what are the lessons high school students should learn regarding the Vietnam War? Unfortunately, Pathways does not provide any. [33] This omission is troubling as

five -sixths of all Americans never take a course in American history after high school. [34]

* * * * *

In a remarkable turn of history, on May 12-13, the current Vietnamese Prime Minister will travel to Washington, D.C., for a summit of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), which was founded in 1967 to, among other things, contain the threat of communism during the Vietnam War. [35] In yet another of the many historical ironies of America’s oscillating rendezvous with Vietnam [36] (officially the “Socialist Republic of Vietnam”), the Biden administration will look to Vietnam at the ASEAN meeting to act as a strategic partner in America's competition with what is perceived to be an aggressive China, particularly in the South China Sea, whose northwest portion (as seen in the map below) is the Gulf of Tonkin, the same body of water over which America sought to counter alleged Vietnamese aggression nearly six decades ago.

Endnotes:

[1] Nguyen, Viet Thanh. Nothing ever dies: Vietnam and the memory of war. (Harvard University Press, 2016). His novel The Sympathizer won the 2016 Pulitzer Prize for fiction. The memory of the war is also preserved at the Vietnam Veterans Memorial on the National Mall in Washington, D.C., which contains over 58,300 names of the men and women who died in connection with their service in Vietnam etched in panels of black granite. The average age of American soldiers in Vietnam was 19. This included 30 year Ardsley resident (and Ardsley Historical Society Board Member) Steve Wittenberg who is quoted in a November 12, 1985, article in The Journal News (“Vietnam dominates Veterans Day Ceremonies'') ” about a reunion he organized of the men he served with in Vietnam (after shipping out in 1968) and their 1 am visit to the memorial which was dedicated in 1982: “It was an emotional gathering that started early Saturday and went into the early hours of Sunday morning. Some of the guys said they spoke more about the war in the last four hours than they had in 17 years.” At about 1 a.m. a group went down to “the wall,” the stark black granite Vietnam Veterans Memorial. “It gave a special release, Wittenberg said. “When you lose someone you have a grave, a place you go and mourn. Some of us never got the chance to mourn. We sat there, touching the wall.”

[2] The 50th-anniversary album cover was of a picture taken by Linda Eastman - the future Linda McCartney - that featured Hendrix playing with children on the Alice in Wonderland sculpture in Central Park in New York City. Eastman’s photo was the originally planned cover for the 1968 album.

[3] The meeting’s link is here: 9/13/21 Meeting of the Tuckahoe Village Board

[4] As explained by Gerald J. De Groot in his refreshing book on the Vietnam War, A Noble Cause? America and the Vietnam War (Harlow, Essex, England: Longman/Pearson Education, 2000), it is common to scapegoat the American soldiers for losing the Vietnam War by holding on to the fantasy that a different type of soldier or a different strategy would have resulted in victory. The unfortunate racial aspect of this belief cannot be ignored, as the Vietnam War was the first American war in which its troops were fully integrated.

[5] Among other things, the Vietnamese call it the “Resistance War Against America.” However, whether it is the Vietnam or the Resistance War, such descriptions obscure the fact the war spilled over into Cambodia and Laos with immense repercussions for the civilian populations in these two countries.

[6] The danger of this civic illiteracy about the Vietnam War has been studied by University of Chicago history professor Kathleen Belew Kathleen Belew | History | The University of Chicago

[7] Among the explanations was that the flag symbolized Trump’s opposition to both communism and China (Vietnam’s historical adversary). The flag’s presence at the January 6th insurrection was strongly condemned by PIVOT, a progressive Vietnamese American advocacy organization. PIVOT CONDEMNS THE DESECRATION OF SOUTH VIETNAM'S FLAG IN THE INSURRECTION AT THE US CAPITOL Interestingly, albeit not unexpectedly, the flag of the defunct Republic of Vietnam is controversial within the Vietnamese community. Even more confounding in using this flag to support Trump is that Trump’s repeatedly calling the novel coronavirus that causes Covid-19 disease the “China virus”has unleashed a wave of hate against members of the Asian American and Pacific Island community. Trump himself avoided being drafted for service in Vietnam five times by relying on four college deferments and a medical deferment for purported bone spurs. Current President Joe Biden similarly used college deferments and later a medical diagnosis of asthma to avoid being drafted during the Vietnam War. Jimi Hendrix purportedly feigned being a homosexual while in the army and obtained an early discharge for “unsuitabilty” in 1962. For an interesting comparison of the Vietnam era draft and Covid-19, see How the quest for COVID-19 vaccine exemptions mirrors the Vietnam War draft

[8] In 2021, Pathways was reviewed in connection with its handling of issues of race in American history, seemingly one of the most controversial. An Analysis of a High School American History Textbook The American Textbook Council (ATC) states, “For secondary-level students, in the hands of a capable teacher, America: Pathways to the Present provides reliable instructional lessons”. However, ATC does not recommend Pathways; instead it urges that high school teachers consider the use of a “college level” textbook. Widely Adopted History Textbooks

[9] Bowen was a medic in Vietnam, He wrote these words in response to a blood-soaked month while on duty. According to a December 14, 1981, special edition of Newsweek, entitled “How Vietnam Changed America,” which profiled Bowen and other Vietnam Veterans a decade after they left the service, the next line in the letter is “ This is about as truthful as you can get.” However, the quote is not original. It was a lament about government service written in 1881 by Konstantin Jirecek (1854-1918), a Czech historian. However, it readily captured the apparent futility of the war as experienced by American military personnel and was often written on personal objects soldiers carried or wore such as helmets.Vietnam War Exhibit in NYC: New Finds, New Stories | THIRTEEN - New York Public Media The words appear on the helmet accompanying this article.

[10] French Indochina was formed in 1887 from the Vietnamese provinces of Annam, Tonkin, Cochinchina (which together form modern Vietnam), and the Kingdom of Cambodia; Laos was added after the Franco-Siamese War in 1893. After the defeat of Nazi Germany, the allied forces (the United States, Britain, and the Soviet Union) agreed at the Potsdam Conference that British forces would be stationed temporarily in the southern part of Vietnam (below the 16th parallel) to disarm the Japanese, who had seized control over Vietnam during World War II. George Wickes, an American whose first language was French, the language of his Belgium mother, was in the OSS. While stationed in Rangoon, he heard from OSS colleagues a mission was being organized to go to Saigon, which was of interest to Wickes as he had studied the Vietnamese language (Annamese) at the University of California at Berkeley as an active duty soldier under the Army Specialized Training Program, which was a highly selective training program established during WW II conducted at American universities. He was told to find OSS member A. Peter Dewey. Dewey was unimpressed that Wickes had studied Annamese as he was looking for people who were fluent in French. Dewey gave Wickes a one-word language test: “how do you say street in French?” The answer is “rue”; however, the letters “r” and “u” are among the most difficult for non-native French speakers to pronounce. Wickes adroitly responded in perfect French and was admitted to Dewey’s team. French was the official language of the government and was used on an everyday basis, including by the Vietnamese. Dewey, whose father was a Congressman, headed the eight-member OSS mission to Saigon, which had the code name “Operation Embankment.” Dewey was tragically killed at age 28 by a Vietnamese irregular (i.e., those fighting the British and the French on the outskirts of Saigon as the Vietnamese had no trained soldiers in the South at that time) using a Japanese weapon in an ambush at a roadblock on September 26, 1945. (Author interview with George Wickes (aged 99), Professor Emeritus of English at the University of Oregon who appeared in Ken Burns’ 2017 documentary film, “The Vietnam War” whose soundtrack begins with Bob Dylan’s “A Hard Rain’s Gonna Fall” and ends with The Beatles’ “Let it Be” ). The circumstances of Dewey’s death remain murky to this day (with speculation it was a case of mistaken identity as Dewey was favorably inclined toward Vietnamese independence, but the vehicle he was driving did not have American insignias) and preternaturally mirror the ambiguity of America’s later involvement in Vietnam. On September 29, 1945, Ho Chi Minh, the leader of the Viet Minh, the leading organization of Vietnamese nationalists seeking independence from France, sent a letter to President Truman expressing sorrow for Dewey’s murder and contained the following: “Allow me to take this opportunity to assure you that the sentiments of friendship and of admiration which our people feel towards the American people and for its representatives here, and which have found enthusiastic expressions on various occasions, do come straight from the bottom of our hearts.” Letter of Ho Chi Minh to Truman Dewey is considered the first American soldier to die in Vietnam. As his body was never recovered, he is arguably the first MIA (missing in action). In 2005, the late Seymour Topping of Scarsdale, an accomplished foreign journalist, authored the novel Fatal Crossroads, titled for the decision by Truman to enable the French to reclaim Vietnam, its “balcony on the Pacific.” In an OSS cable Dewey wrote two days before his death, he prophetically offered this analysis of Vietnam in the fall of 1945, which is now viewed as the first unheard warning against American military involvement in Vietnam: “Cochinchina {the southern province of Vietnam] is burning, the French and the British are finished here, and we out to clear out of Southeast Asia.” British author Graham Greene’s 1955 novel, The Quiet American, centers around a CIA agent working undercover in Vietnam during the waning years of the French colonial era.

[11] This would include ending French sovereignty over Indochina, something President Franklin Roosevelt favored. In exchange for Roosevelt’s opposition to the continued presence of the French in Indochina, the Viet Minh assisted the OSS in repatriating American and allied prisoners of war held by the Japanese. However, upon FDR’s death, his successor, Truman, reversed American policy and to the wonderment of the crewmembers of the Victory, to whom the Vietnamese all spoke of their hatred of the French, “brought the French invaders back.” Henry Dooley, crewmember S.S. Georgetown Victory, 1945 (quoted in Gillen) (Chapter III)

[12] The Diplomat was located at 108 West 34th Street. The rock band KISS booked The Diplomat themselves for some of their earliest Manhattan dates — July 13 and August 10, 1973. Within two weeks after their second show, KISS signed with Neil Bogart's recently established Casablanca Records, which incongruously was primarily a label for disco music. The Diplomat was demolished in 1994.

[13] American involvement in the “Vietnam War” is stated in Pathways to cover only the years 1954-1975.This is misleading. Americans provided the French with extensive military assistance beginning with the Truman administration in 1945 until the Viet Minh defeated the French in 1954 at the decisive battle of Ben Dien Phu in northwest Vietnam in what is known as the First Indochina War. Incredibly, American officials loosely offered the French an atomic bomb for use in their flailing effort to defeat the Vietnamese nationalist forces led by General Vo Nguyen Giap, who is considered one of the 20th century’s greatest military strategists.

[14] A war's secret history finally emerges - National Constitution Center Officially titled “History of U.S. Decision-Making in Vietnam, 1945–68,” the Pentagon Papers were commissioned by then-Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara after he had developed doubts about the wisdom of the war. The use of the word “secret” to describe the Pentagon Papers conceals the fact they contained the “true” history of the Vietnam War as opposed to the lies the American public was told.

[15] Discussion of the Pentagon Papers only appears in a sidebar to Pathway's main text although the papers filled 47 volumes, covering the administrations of President Franklin D. Roosevelt to President Lyndon B. Johnson over 7000 pages chronicling how the United States got itself mired in a long, costly war in a small Southeast Asian country of questionable strategic importance. With the Pentagon Papers’ revelations, the U.S. public’s trust in the government was forever diminished. Elizabeth Baker, The Secrets and Lies of the Vietnam War, Exposed in One Epic Document (June 9, 2021) (Updated August 1, 2021)

[16] Two years later in a letter to the Editor of The New York Times, Ardsley’s David Glixon would express his objection to the undeclared Vietnam War. .David M. Glixon – Ardsley's Man of Letters The Gulf of Tonkin incident has been studied intensively by Congress, newsmen, and scholars. Two congressional studies are: Hearings before the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations, The Gulf of Tonkin, the 1964 Incidents, 90th Cong, 2d Sess, with the Hon. Robert S. McNamara on February 20, 1968, and Part II (with supplementary documents to the study of February 20, 1968), February 16, 1968. The subject is also addressed in the following six books: Joseph C. Goulden, Truth is the First Casualty: The Gulf of Tonkin Affair—Illusion and Reality, (Chicago, 1969); John Galloway, The Gulf of Tonkin Resolution (Rutherford, N.J., 1970); Eugene G. Windcy, Tonkin Gulf (New York, 1971); Anthony Austin, The President’s War (New York, 1971); Stanley Karnow, Vietnam: A History (New York, 1983), pp 369–76; and Robert S. McNamara and Brian VanDeMark, In Retrospect: The Lessons and Tragedy of Vietnam (New York, 1995), pp 132–36.Gradual Failure : The Air War Over North Vietnam :1965-1966 The Methodist Federation for Social Action (now in Detroit), sponsors a Lee and Mae Ball Award.The Lee and Mae Ball Award | Rio Texas Methodist Federation for Social Action

[17] Karnow, Stanley. 1983. Vietnam: A History. New York, N.Y.: Penguin Books. p. 380.

[18] Elizabeth Baker, The Secrets and Lies of the Vietnam War, Exposed in One Epic Document (June 9, 2021) (Updated August 1, 2021)

[19] See David Steigerwald, The Sixties and the End of Modern America (London, 1995), pp. 106-7.

[20] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OC1Ru2p8OfU King’s speech against the war broke his strong relationship with President Johnson and other white allies. Life magazine called the speech “demagogic slander that sounded like a script for Radio Hanoi (the North Vietnamese propaganda radio station). King was assassinated exactly one year later while standing on the balcony of the Lorraine Motel in Memphis where he was preparing for a march in support of the city’s striking sanitation workers. On April 7, President Johnson called for a national day of mourning. King visited Westchester County a dozen times during his lifetime. Andy Bass, "Martin Luther King, Jr.: Visits to Westchester, 1956-1967," Spring 2018 issue of The Westchester Historian, the quarterly of the Westchester County Historical Society.

[21] Patti (1913-1998) authored Why Vietnam?: Prelude to America's Albatross (University of California Press, 1982). It is the most frequently cited source for Dewey’s prophetic 1945 cable about the burning of Cochinchina. A search for the original cable, which is cited in numerous books, dissertations, and articles is being made in the National Archives in Washington, D.C., as well as Patti’s research archives in Central Florida University and in private archives. In a personal interview with Nancy Hoppin, Dewey’s daughter, she acknowledged being aware of the cable but did not have a copy. When the author suggested its “disappearance” was part of the mystery of Vietnam, she replied, “perhaps.”All OSS cables sent from Saigon were coded by a cryptographer and then decoded upon arrival in Kandy. They would then be sent encoded to Washington as the OSS did not transmit cables “in the clear.” (interview with George Wickes)

[22] One of the most famous or perhaps infamous images of the Vietnam War, if not the 20th Century, is John Fila’s picture of 14-year-old runaway Mary Ann Vecchio screaming while kneeling over the dead body of 20-year old Jeffrey Miller, one of the victims of the Kent State shootings, which won him a Pulitzer Prize in 1971. Miller’s cremains are interred in a niche in the community mausoleum at Ferncliff, which is within the boundary of the Ardsley School District. Jeffrey Glenn Miller (1950-1970) - Find a Grave Memorial The image appears in Pathways.

[23] The Tet Offensive was a coordinated series of North Vietnamese attacks on more than 100 cities and outposts in South Vietnam. The offensive was an attempt to incite rebellion among the South Vietnamese population and encourage the United States to scale back its involvement in the Vietnam War.https://www.britannica.com/topic/Tet-Offensive Although the Tet Offensive was seen as a military disaster for the North, paradoxically it was a psychological victory by convincing the American public that there might not be any “light at the end of the tunnel” as suggested by American military officials a year before in 1967. GENERAL DISPUTES QUOTE IN CBS TRIAL - The New York Times Almost two decades earlier, North Vietnam’s General Giap had predicted a long war with the French and would later incorporate his same methods of protracted warfare against the Americans who relied too heavily on offensive search-and-destroy missions: “The enemy will pass slowly from the offensive to the defensive. The blitzkrieg will transform itself into a war of long duration. Thus, the enemy will be caught in a dilemma: He has to drag out the war in order to win it and does not possess, on the other hand, the psychological and political means to fight a long-drawn-out war.” cited in Bernard B. Fall, Street without Joy. Indochina at war, 1946-54 (Harrisburg: Stackpole Co. 1961). Four decades later, Fall’s book would end up on the reading list for officers during the Iraq war (another war begun on false premises, to wit, the presence of weapons of mass destruction) The Reporter Who Warned Us Not to Invade Vietnam 10 Years Before the Gulf of Tonkin | The Nation. Significantly, Giap opposed the Tet Offensive and preferred relying on his strategy of using time to grind down the American military and hope domestic impatience with what seemed to be an unwinnable war would force its end. Interestingly, this was the same strategy employed by George Washington when confronting the British in the American Revolutionary War. Six Months or Forever: Doctrine to Defeat an Enemy Whose Center of Gravity is Time | Small Wars Journal

[24] My Lai was a hamlet in the Village of Son My. What the Pathways textbook means by using the word “sometimes” is unclear. While some have contended that My Lai was a rare event committed by a poorly led group of soldiers, more convincing evidence indicates such events as My Lai were frequent and that My Lai was unique only in terms of the number of innocent civilians killed. Exposing Evil: My Lai, the Media, and American Atrocities in Asia, 1941-1975

[25] Many in Meadlo’s community didn’t see him as blameworthy. “How can you newspaper people blame Paul David? He was under orders. He had to do what his officer told him. Quoted in J. Anthony Lukas, “Meadlo’s Home Town Regards Him as Blameless,” New York Times, Nov. 26, 1969.

[26] The Peers Report Thompson endured death threats, PTSD, and years of ostracism. Tragically, one of his crew died in a helicopter crash three weeks after My Lai. Hugh Thompson, 62, Who Saved Civilians at My Lai, Dies - The New York Times

[27] While not coined until the first Earth Day in April 1970, the phrase “We have met the enemy and he is us” was quickly adopted by those opposed to the Vietnam War. It appears as a perfect metaphor for the encounter between Calley and Thompson.

[28] Marciano, John. “Chapter 5: Civic Illiteracy and American History Textbooks: The U.S.-Vietnam War.” Counterpoints 23 (1997): 107–43. http://www.jstor.org/stable/42975126.

[29] https://www.sandiegouniontribune.com/opinion/commentary/story/2021-04-14/opinion-vietnam-veterans-against-the-war-capitol-1971 Vietnam, the United States as a country has not been at war, only its military due to the creation of the all volunteer military that followed in the wake of the Vietnam War.

[30] A corollary is that few of our national leaders have any military experience and ask the armed forces to do things they cannot do.

[31] The New York Times, November 20, 2018. On April 1, 1973, as the fall of Saigon was imminent, George Ball, an American State Department official in the Kennedy and Johnson administrations who opposed military escalation of the war, in an essay entitled “The Lessons of Vietnam,” wrote in The New York Times: “South Vietnam was never a nation but an improvisation—a geographical designation for what General De Gaulle once described to me as a piece of “rotten country.” It was an area that, merely by a caprice of history, fell south of what the Geneva Conference designated in 1954 as a temporary demarcation line and specifically not “a political or territorial boundary.” Arbitrarily carved out of what had been Cochin‐China and a part of the old Kingdom of Annam, it embodied no cultural or ethnic logic. Political power was fragmented—split among Catholics, Buddhists, Hoa Haos, Cao Dais and Binh Xuyens, all at odds with one another, while the Montagnard tribes and the Khmer and Shan populations lived separate lives without interest in, or knowledge of, infighting in Saigon.” The Lessons of Vietnam - The New York Times

[32] "I believe that Vietnam was what we had instead of joyful childhoods," American writer and war correspondent Michael Herr said in his acclaimed Vietnam War book "Dispatches." Ardsleyan Steve Wittenberg (who served in B Company of the 2nd Battalion, 8th Infantry Regiment of the 4th Infantry Division) in the central highlands of Vietnam expressed a similar sentiment in an article appearing in the Billings Gazette (August 5, 2000).

[33] Readers seeking an explanation should not only read George Ball's 1973 essay, but also visit the New York Historical Society's superb online exhibition on the Vietnam War.The Vietnam War: 1945 – 1975 | New-York Historical Society

[34] Historical Reconciliation and United States History Textbooks about Vietnam