Tewanima Ran Here

According to Dutch maps from nearly four centuries ago, the Native Americans who inhabited modern-day Ardsley were known as the Weckquaesgeek. [1] But who were the Weekquaesgeeks? The same question can be asked about the Dutch settlers of North America. Many were not ethnically Dutch but a cohort of other Europeans and enslaved and freed Africans. [2] However, unlike the Dutch, there is no precise date when the Native Americans first arrived in present-day Ardsley. The inability to fix a certain date when the Native Americans first came to our area stems primarily from the brutal wars between Native Americans and the Dutch (and other Europeans), as well as among Native Americans themselves, combined with the ravaging impact of disease so that by the time of the American Revolution, most of the indigenous people who lived in our area had disappeared from death, merger with other tribes, or exile. [3] As a result, much of their early history was lost or buried, especially in the 19th-century when Native American sites were carelessly destroyed during the building of roads and the Croton aqueducts. [4]

Of course, few Dutch mapmakers spoke the language of the Native Americans they encountered. Consequently, Native American names on maps were frequently determined by the geographical terrain they occupied rather than their place of origin. Weekquasegeek, for example, is a local place name that was once assumed to refer to the place of birch bark trees. Other linguists contend it means "at the end of the swamp." Wicker’s Creek on the Hudson River in Dobbs Ferry is a Native American oyster shell mound or midden (overseen by Friends of the Wicker’s Creek Archaeological Site) [5] purportedly dating back to between 8-9000 years. In Part III (entitled Aboriginal Place Names of the County of Westchester) of Aboriginal Westchester, a six-part manuscript edited by noted early 20th-century Native American scholar Leslie Verne Case, contributor Reginald Pelham Bolton doubted that Weekquasegeek referred to something “at the end of a marsh or a bog,” as no such marsh or bog existed in Dobbs Ferry (ostensibly the location of the chieftaincy of the tribe). Further, as Weekquasegeek territory extended from Chappaqua to Manhattan and between the banks of the Hudson and Bronx Rivers, the name given to the tribe by the Dutch was unsatisfactory. [6]

Anthropologist and prominent Native American scholar Robert S. Grumet argues in a recent book that the Native Americans who lived in our area are more appropriately called the Munsee Indians, which reflected both the language they spoke and certain cultural practices. [7]

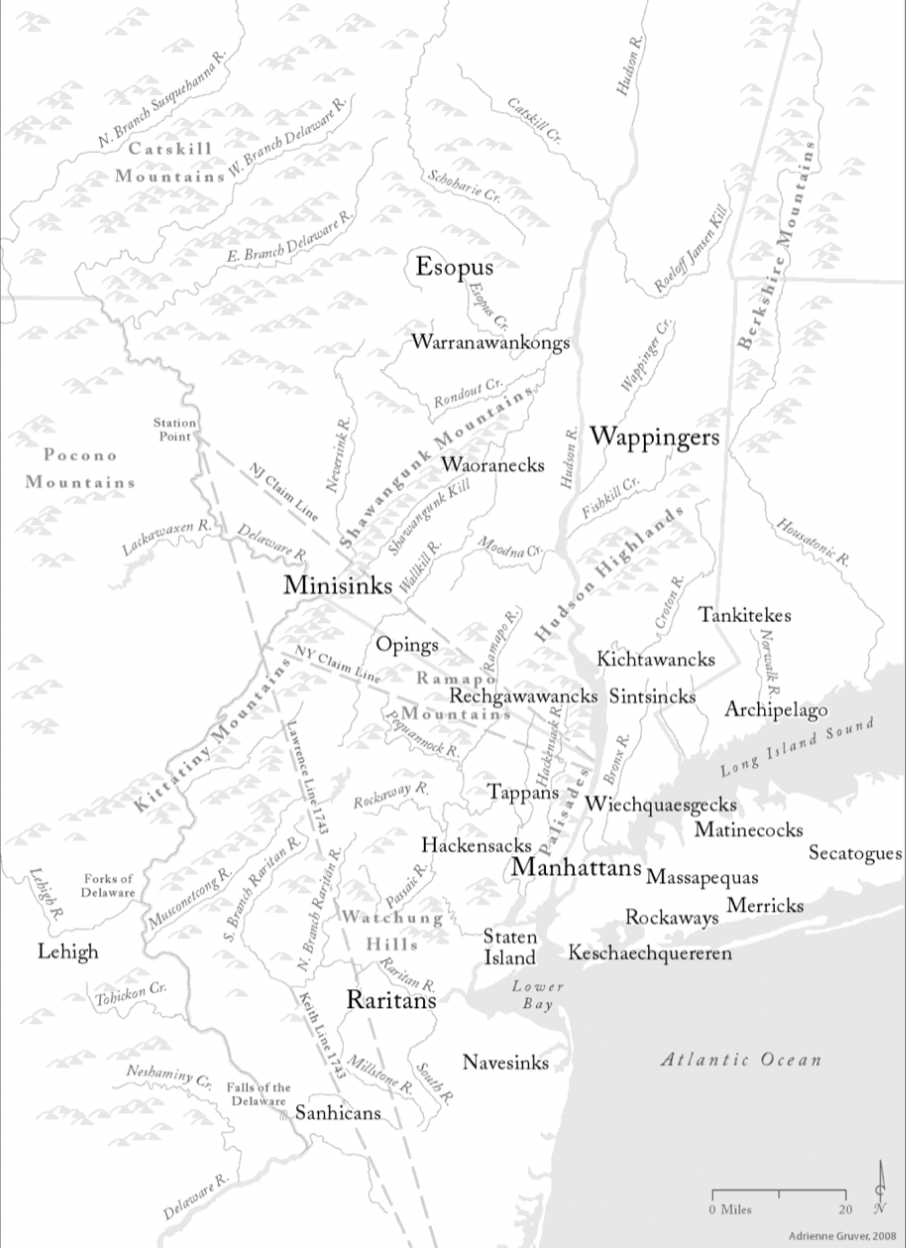

As depicted in the map below, the homeland of the Munsees,

“lay across a twelve-thousand-square expanse of tidewater and timberland that stretched from the Atlantic Ocean across piedmont foothills and ridge valleys to the Appalachian Mountains one hundred miles further inland. Their country took in the westernmost reaches of Long Island Sound and present-day Connecticut, extended across New York Harbor and its adjoining hinterland, and reached over the Hudson Highlands and through the Great Valley of southeastern New York and northern New Jersey to northeastern Pennsylvania’s Pocono Plateau and Lehigh Valley. The Catskill Mountains marked its northern borders, the Berkshires, the Taconic Mountains, and Central Long Island pine barrens framed the territory’s eastern limits. New Jersey’s pinelands stood watch over the southern frontiers. The upland divide separating the Delaware from the Susquehanna river drainages formed its western boundary.” [8]

Modern scholars of the Munsee Indians agree that following their encounter with the Europeans, beginning with the arrival of Henry Hudson in 1609, the Munsees had by the 17th-century loosely organized themselves into bands with the names shown on the below map such as the Wiechquaseeks. Whether the Munsees understood themselves to be known by the group names (which scholars equate to a form of village identity) is unlikely. [9]

Curiously, the Munsees were not a maritime people. Instead, they followed a deeply rooted way of life based on hunting, fishing, foraging, and farming in fields, forests, and streams that stretched inland from the region’s beaches and riverbanks. [10]

In addition to Leslie Verne Case and Bolton, W.R. Blackie, an early 20th-century minister of Ardsley’s Methodist Church, who is considered the third wise man of Westchester County’s Native American history, conducted extensive archeological investigations (often sponsored by the Museum of the American Indian) of the Native American presence in our region when it was predominantly rural. As plows tilled the earth of Ardsley’s farms, Blackie would follow them and search for Native American artifacts.

Blackie’s section of Aboriginal Westchester describes three Native American camp sites in Ardsley, one on the bank of the Saw Mill River (and likely in the vicinity of Woodlands Lake where the Saw Mill River and Dobbs Ferry Road intersect) [11] and two on the former estate of Adolph Lewisohn (one on the eastern side bordering the bank of the Sprain brook, and the other near Orlando Avenue near what Blackie identifies as a “fine spring”). [12] A large portion of Blackie’s collection of the Native American artifacts he found in Ardsley is kept in The New York State Museum in Albany. One significant item in Blackie’s museum collection is a stone tool (shown below) known as a gouge.

In determining that what appears to be a mere rock is a Native American tool, Dr. Jonathan Lothrop, The New York State Museum’s Curator of Archeology, in an email to the author, explains that:

This is a tool known as a gouge, made by pecking and then laborious grinding to shape and create a sharp concave bit (on the left side of this image). Native Americans used such tools in New York for several thousand years. They were typically hafted on a wood handle set perpendicular to the axis of the gouge and would have been used for woodworking tasks, potentially such as dugout canoe manufacture. The evidence that this was a tool/artifact can be traced from both its manufacture and use. [The] dimpling that you see around most of the surface of this tool is from the initial pecking with a pointed hammer stone to roughly shape the tough metamorphic stone that this artifact is made of. Following overall shaping, the artisan ground down the working edge on the left side using an abrader stone to grind the bit into shape and sharpen it. Traces of use on this tool include rounding/dulling of the bit and occasional striations extending up from the bit, produced by repetitive use in woodworking. During their use, these gouges likely would have been resharpened multiple times until their final discard. [13]

The accession record of The New York State Museum for the gouge indicates it was found by Rev. Blackie along Ardsley Road, which is the name of Ashford Avenue as it continues in an easterly direction after it intersects with Sprain Road. The road’s name change from Ashford Avenue to Ardsley Road remains confusing to drivers. Concern over this issue is not new. As reported in the below section of the Irvington Gazette (January 25, 1924), the Town of Greenburgh suggested that the Edgemont Association in Greenburgh take up the issue with the village boards of Ardsley and Dobbs Ferry as to the advisability of changing the entire name of Ashford Avenue and its former continuation as Platt Avenue to Ardsley Road.

However, they were only partly successful in changing Platt Avenue to Ardsley Road, as reported in the April 12, 1924, Scarsdale Inquirer:

* * * * *

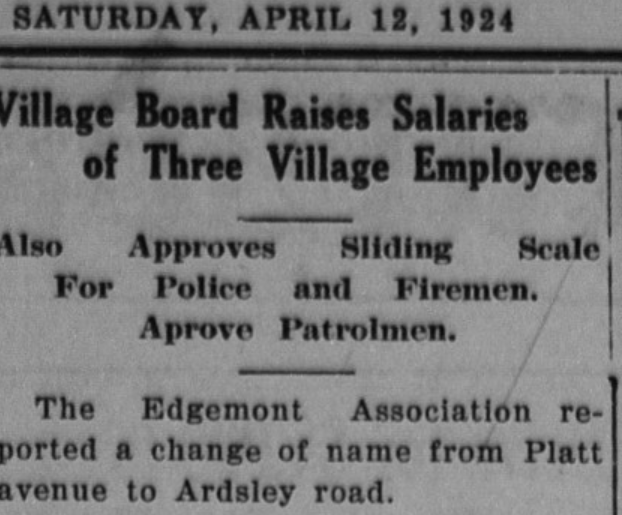

The March 1991 edition of The Ferryman, the newsletter of the Dobbs Ferry Historical Society, contends that Ashford Avenue was originally an Indian trail connecting the Hudson River to the Native American hunting grounds of Thirty Deer Ridge, where Ashford Avenue meets Sprain Road and becomes Ardsley Road. [14] The below excerpt from surveyor Sidney & Neff’s 1851 map of Westchester County shows that what is now Ashford Road was the only major east-west route from Dobbs Ferry through what was later Ardsley (as indicated by J.King’s building where Captain John King (1807-1885) operated one of the three pickle factories [15] situated in Ashford as Ardsley was then known, in the mid to late 1800s, to the Sprain brook (see the letter “k” representing the last letter in “brook” under the word “Ridge” which is part of Thirty Deer Ridge found in the lower right corner of the map ). According to Arthur Silliman’s “A Short, Informal History of Ardsley, NY,” Ashford Avenue is named for Ashford, Kent County, England, the birthplace of Captain John King, an early settler and sloop owner “who raised cucumbers which he processed in his own factory at the foot of King Street.” The factory, Silliman reports, closed after King’s 70th birthday in 1878. Captain John King and his wife, Eliza Ann Dobbs (who was related to the namesake of Dobbs Ferry) are buried in the Greenville Community Reformed Church cemetery behind the stip mall at 590 Central Park Avenue near Old Army Road in Edgemont. Unfortunaely their graves are in poor condtion and you can only barely make out the name of Captain John King. Also buried nearby is Ardsleynan Willam E. Slocum, a civil war veteran who survived the notortious Confederate Civil War prison at Andersonville. Beginning in 1872, and for the ensuing four decades, he served as head of the Ardsley Schools. From roughly 1842 until 1958, a clapboard church stood on Central Avenue in front of the cemetery which is on land donated the Church in 1870 by Mrs. Mary A. Tompkins. In 1958, a. new brick church builidng was built on Ardsley Road (No. 270). In 1872, King’s son Richard Lawrence King moved to Waterford, Michigan, where he became a highly successful farmer and sold pickles under the trade name Westchester Pickles as depicted below. Percy King Road in Waterford is named for Richard’s son who acquired a nearby 148-acre parcel. [16]

The 1851 map also shows the Storms family property on Ashford Avenue just west of the Saw Mill River, which is shown in the linked edition of The Ferryman. A descendant of the Storms family, Dr. Harold Storms (1889-1956) was a beloved “county doctor” for forty years in Dobbs Ferry and the great-grandson of Captain John King. Dr. Storms’ son Harold Ackerman Storms, Jr. was killed in action during the Korean War on July 10, 1953. (The Captain's eldest daughter Maria Elizabeth had married Edmund A. Ackerman who was Dobbs Ferry’s first United States Postmaster).

The 1851 map corresponds with the below hand-drawn map of the business center of Ashford as the area was known in the 1860s, showing the schoolhouse, the blacksmith shop, the Lawrence shoe shop, the hotel, and the properties of King (numbers 18,19, and 21), Losee (number 20) and Lefurgy (number 22) along Ashford Avenue. The letter “A” on the map identifies the Saw Mill River in the alternative as the “Neperhan,” which may derive from a name applied to the name of a Native American village (i.e., Nepperamack) in the vicinity of present-day Yonkers.

Forty years later, the below 1893 map shows a more robust downtown Ardsley on the cusp of its incorporation in 1896 into a village as well as the 140 acre Acker family parcel. The Ackers were one of the oldest families in Ardsley and traced their lineage to the area's original Dutch settlers. Platt Avenue is visible on the far right side.

According to Silliman’s A Short, Informal History of Ardsley, Rev. Blackie (whose collection in Albany contains 369 artifacts) was given free rein to explore the nearly 400-acre Lewisohn Estate, which bordered the Sprain brook. Over a century ago, on one of his visits to Lewisohn’s property, he discovered a bird-shaped object, shown below, which, in 1918, he donated to the National Museum of the American Indian, Smithsonian Institution. [17]

In an email to the author (lightly edited for clarity), Dr. Lorthrop explained that:

such figurative artifacts were made by Native Americans in Eastern North America roughly 2500 years ago (500 BC). In nearly all cases, they consist of a stylized representation of a bird, showing either the head and body or just the head and shoulders. Bird stones were usually made of hard metamorphic stone by a labor-intensive process of pecking, grinding, and polishing. These artifacts always exhibit a flat surface on the bottom, and one of the final steps in manufacture was the drilling of paired holes at oblique angles at the front and back of the flat base. These holes suggest that bird stones were typically lashed to a flat surface. The purpose of bird stones is uncertain; archaeologists have speculated a wide range of functions. [18] Clearly, however, there is a distinctive aesthetic quality to these artifacts. [19]

* * * * *

A scant 150 years after Henry Hudson, an English navigator and sea explorer who, in 1608 and 1609, sought a trade route to Asia for the Dutch East India Company, arrived in what would destined to be a body of water named for him, the Native Americans in the lower Hudson River Valley had nearly disappeared. However, three hundred years after Hudson’s journey to what would first become New Amsterdam and later New York, in 1908, a historic marathon race heralded the arrival in Ardsley of legendary Native American long-distance runner Louis Tewanima (1888-1969). [20]

Although now overshadowed by the Boston and New York City Marathons, the course of the first American marathon (held on September 19, 1896, following the successful revival in the summer of 1896 of the Olympics in Athens, Greece was predominantly in Westchester County (the 25-mile footrace began in Stamford, Connecticut, and traversed down to Columbia University’s Oval (in the Bronx) along the Boston Post Road through the municipalities of Port Chester, Rye, Harrison, Mamaroneck, Larchmont, New Rochelle, and Eastchester. [21]

As reported in the below article in the Dobbs Ferry Register, the second running of the Yonkers Marathon in 1908 (the second oldest American marathon race after the Boston Marathon, which began in 1897) featured seven runners who had competed in the Boston Marathon along with three Native Americans including Tewanima. [22]

The Dobbs Ferry Register article did not mention that Tewamina (a Hopi) and his fellow Native American teammate John Coon were running on behalf of the Carlisle Indian Industrial School. The Carlisle School was an off-reservation boarding school that operated from 1879 until the entry of the United States in World War I. Its purpose was to foster the cultural assimilation of Native Americans and rapid immersion into “white culture” by “ first doing away with all outward signs of tribal life that the children brought with them. The long braids worn by Indian boys were cut off. The children were made to wear standard uniforms. The children were given new “white” names, including surnames, as it was felt this would help when they inherited property. Traditional Native foods were abandoned, forcing students to acquire the food rites of white society, including the use of knives, forks, spoons, napkins and tablecloths. In addition, students were forbidden to speak their Native languages, even to each other. The Carlisle school rewarded those who refrained from speaking their own language; most other boarding schools relied on punishment to achieve this aim.” [23]

Tewanima in Hat and Suit (click link for more information)

While the underlying (albeit pernicious) philosophy behind the boarding schools was known as “Kill the Indian, save the man,” the forced placement of Native American children in boarding schools like Carlisle was part of an effort to save what some 19th-century social reformers saw as a species of people whose only chance of survival or “uplift’ was to forcibly relocate their children (described as “the nation’s wards” in The Indian Craftsman, a “magazine not only about Indians but mainly by Indians” published by the Carlisle School) [24] and “civilize” them by requiring them to abandon their Native American cultural practices. In the view of the boarding school promoters, assimilation was considered a better choice than the prevailing American attitude toward Native Americans of removal or extermination. [25] Some advocates of the boarding schools duplicitously argued that the Native Americans would now learn to read English so they could understand the treaties they had signed. [26]

* * * * *

In its account of the second running of the Yonkers Marathon race, The New York Times reported that it was “the biggest and probably the most spectacular event of its kind ever held in America,” which was witnessed by a huge and enthusiastic crowd. [27] Public interest in the race was not unexpected as American Marathon scholar Pamela Cooper observed in her seminal book, The American Marathon, “New Yorkers have been intrigued by footraces since the early nineteenth century.” [28] As for the course, it was

“...about twenty-six miles, twenty-one miles being across country, the route being from Getty Square, Yonkers, along South Broadway to Valentine Lane, west to Riverdale Avenue, thence northerly along Riverdale Avenue and Warburton Avenue, through Hastings and Dobbs Ferry, thence east on Ashford Avenue to inland Ardsley, over Daisy Avenue [now Heatherdell] to Hartsdale Avenue, to Central Avenue, thence south to the Empire City Track.”

J.F. CROWLEY WINS YONKERS MARATHON; Irish-American Runner Leads Big Field Over Westchester County Roads. "SAM" MELLOR IS SECOND Tewanina, the Indian, Finishes Fourth in Fast Contest -- Large Crowd at Empire City Track.

Although Tewamina finished fourth, his appearance in Ardsley, 2300 miles from his birthplace on the Hopi Reservation in northeastern Arizona, preternaturally restored the physical presence of Native Americans to lands where they had existed for thousands of years but had disappeared from over 150 years earlier. According to the below report on the race in the New-York Tribune (November 27, 1908), Tewanina, who was favored to win, led the race from Ardsley to Hartsdale.

“Little Rocky Mountain,” about ten and a half miles from the starting point, proved a rocky road for more than one runner; all of them had to slow up, some stopped altogether, but those of class forged along and picked their way to the front. Many thought Tewanima would crack here, but the Indian was running strongly along and continued in front. On the way from Ardsley to Hartsdale Tewanima still set the pace, with Coon close up. Thirteen miles out Mellor joined the two Indians, and the old champion ran along in grand style. They were joined a mile later by Crowley and Fowler. Coon began to show signs of the effects of the terrific pace over the heavy road.

Below is a segment of a 1908 map of Greenburgh showing the race course in Ardsley as it traverses easterly from Ashford Avenue in Dobbs Ferry through downtown Ardsley along Daisy Road (site of the Lewisohn property), over the Sprain Brook and continuing on the Road to Harts Corners (now Sprain Road) to Hartsdale Avenue which intersects with Central Avenue.

⇒ East

A few months earlier, in the summer of 1908, Tewanima represented the United States in the London Olympics, where he placed ninth in the marathon. [29] His silver medal in the 10,000 meters in the 1912 Stockholm Olympics set the record (32:06.6) for the United States, which stood for fifty-two years until another Native American, Billy Mills, a Lakota Sioux from the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation, broke the record when he won the gold medal at the 1964 Tokyo Olympics. Paradoxically, in London and Stockholm, Tewamina was not an American citizen, “yet he represented the United States in two world Olympics as a great “American” athlete.”

1912 Carlisle Track Uniform (click link for more information)

Tewanima’s navigation of his Native American identity on the national and global athletic stage (as well as the contested issue of whether the Hopi were granted American citizenship under the 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo between the United States of America and the Mexican Republic, which ended the Mexican-American War (1846-1869)) has drawn scholarly attention. [30] The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo resulted in the third-largest territorial acquisition by the United States (surpassed only by the Louisiana Purchase (1803) and the Alaska Purchase (1867)).

After the Olympics, Tewanima returned to Arizona and spent the remainder of his life on the Hopi Reservation in Second Mesa [Arizona]. In a 1940 memoir penned by Carlisle School attendee Jim Thorpe, considered America’s most outstanding athlete of the 20th-century, he recalled “the day Carlisle had a dual meet with the Lafayette College 20 man team. We had only three Indians (Me) Frank Mount Pleasant, and Louis Tewanima. Tewanima’s reply was; Me run fast good. All Hopis run fast good. Almost immediately, Tewanima proceeded to clean up everything America had to offer in the 10-mile and 15-mile races.”

* * * * *

In 1983, Westchester County observed its Tricentennial (i.e., the 300th anniversary of its founding in 1683). The Village of Ardsley’s anticipated participation in the planned event led to the founding of the Ardsley Historical Society (“Ardsley Historical Society Founded,” The Enterprise, May 27, 1982). As further reported in The Enterprise (February 10, 1983), the Ardsley Historical Society invited members of the Mohawk Indians to the County’s celebration (which was held in Macy Park on Saw Mill River Road in Ardsley) as representatives of the Native Americans who once inhabited Ardsley no longer existed due to what was described in the article as “the European incursion.” The Tricentennial was held on Saturday, June 11th, and nine Mohawks attended. While in Ardsley, they stayed at the homes of local residents. Additionally, a Tricentennial marathon race was held at Ardsley High School’s track, where runners obtained sponsors of $1 for each mile run (The Enterprise, May 5, 1983). [31]

The below-faded historical marker in front of 2121 Saw Mill River Road on the Ardsley/Elmsford border is all that remains of the Tricentennial (other than the Records of the Westchester Tricentennial Committee 1980-1983, which are stored in folders about one hundred feet north of this marker at the Westchester County Archives at 2199 Saw Mill River Road).

* * * * *

On September 4, 2022, The Hopi Athletic Association will host the 49th annual Louis Tewanima Memorial Footrace on the Hopi Reservation in Second Mesa. [32]

Endnotes:

[1] In the absence of a consensus on how to describe the indigenous people of North America, the term Native American will be used. The name Weekquasegeek itself has numerous spellings including, Wiechquasegeek. Its meaning remains disputed.

[2] David Steven Cohen, "How Dutch were the Dutch of New Netherland?", New York History 62 (January 1981): 43-60

[3] The Weekquasegeek, an undated but widely cited study written by Doris Darlington Cohen (1930-2020) for the Ardsley Historical Society, relates that the remnants of the tribe, which traces its ancestry to present-day Ardsley,, now live in parts of Massachusetts and Canada. Descendants are also found in Wisconsin and Oklahoma. According to her obituary, Cohen's study of the Weekquasegeek sparked a passion for studying Native American culture. https://www.edwardlkellyfuneralhome.com/obituary/Doris-Cohen Cohen’s study was recently discussed in a historical paper written by Newport High School student Amelia Chiu which was accessed from the Ardsley Historical Society’s website. The Dutch Encounter: How Miscommunications in the New World Contributed to an Era of Exploitation Newport High School is in Bellevue, Washington, a suburb of Seattle.

[4] Archaeologists have devised a cultural chronology for North America in which the Precontact era (i.e., the period before the arrival in North America of European explorers) is divided into four main periods, the Paleo-Indian (c. 12,000-10,000 years ago), Archaic (c. 10,000-2,700 years ago), Woodland (c. 2,700-500 years ago), and Contact (500-300 years ago).

[6] Aboriginal Westchester (pages 270-271). The history of Aborignal Westchester is discussed in W.R. Blackie/American Indians in Ardsley Reproduction of any portion of Aboriginal Westchester is done so by the kind permission of the Dobbs Ferry Historical Society, Dobbs Ferry, New York.

[7] Richter, Daniel K., Grumet, Robert S. The Munsee Indians: A History. (United States: University of Oklahoma Press, 2014).

[8] Richter and Grumet,, supra, p. 4

[9] Otto, Paul., The Dutch-Munsee Encounter in America: The Struggle for Sovereignty in the Hudson Valley (European Expansion & Global Interaction, 3) ( Berghahn Books, 2006) The Dutch-Munsee Encounter

[10] Richter and Grumet, supra, p. 4

[11] In 1978, Peggy Case, Leslie Verne Case’s daughter, in conjunction with the Junior League, created a map and booklet of Westchester’s Colonial and Native American Heritage which marked this location as a Native American burial ground. https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1978/06/04/issue.html

[12] Indian Occupation of Westchester County, New York (contained in Part IV of Aboriginal Westchester), p. 285. Blackie’s investigations uncovered several other Native American sites in Ardsley, including one near New Croton Aqueduct Shaft No. 14, which is adjacent to the parking lot of the Ardsley Public Library on American Legion Drive. Another indigenous site was a village and burial mound near the center of the Village of Ardsley, just northeast of the location of Shaft No. 14. The Cultural Resource Assessment for the rehabilitation of the New Croton Aqueduct which took place in the early part of the 21st-century contains an extensive discussion of the various eras (described in footnote four above) of the Native American presence in our area, including near Shafts 13 (in Greenburgh), and 14 and 14a (in Ardsley) as well as the history of the building of the New Croton Aqueduct which opened in 1890. http://s-media.nyc.gov/agencies/lpc/arch_reports/820_B.pdf (VI-42) The May 7, 1887, edition of The Eastern State Journal reported that four “colored” workers at Shaft 14 became ill with smallpox. In addition to disease, injury, death, and low wages were commonly experienced by the laborers who built the New Croton Aqueduct. As a September 5, 1886, article in The Sun newspaper entitled “Aqueduct Slavery” stated, “The man who works in the tunnels and shafts of the new aqueduct is in more danger than a soldier on the battle field. The hovels in which he is crowded with scores of his fellows are worse than prison pens. The medical attendance he is forced to pay for he does not get. The food he should have and is forced to pay for he does not get. The wages which he is told will be paid him and which he earns he does not get. The only thing he does get in full is transportation away from the shafts when he is maimed, and the grave hole into which he is dumped when he is killed.”

[13] Email correspondence dated March 4, 2021, to the author from Dr. Lothrop (lightly edited for clarity), whose research is focused on how and when Native Americans colonized and then settled the New York region from near the end of the Pleistocene or Ice Age into the early Holocene, between about 11,000 and 8000 B.C. Jonathan Lothrop bio

[14] The Ferryman March 1991 Local historian Henrietta Toth asserts Ashford Avenue, Ardsley’s major thoroughfare, was once called the Road to Dobbs Ferry and developed from a Native American trail that connected the Hudson River with the Long Island Sound. Bee Local: Focus on Ardsley

[15] “The term pickles is generally used by dealers and growers to mean preserved cucumbers. The Westchester County cucumbers are considered the best by the trade, being solid and brittle. The packing-houses in this county are located at Mount Vernon, New Rochelle, Dobbs Ferry, Cbappaqua, White Plains, Sing Sing, and Ashford. The cucumbers are gathered between three and six inches long, and taken by the farmers in barrels to the salting-houses, where they are dumped into a large wooden tank which contains coarse salt and a little water. The cucumbers should be salted within twelve hours after being gathered, and are better if salted immediately. Tbe brine is kept skimmed, and salt and water are occasionally added. In about three weeks the pickles stop fermenting, and are ready to be prepared for market.”How Pickles are Prepared.” The Eastern State Journal (June 18, 1882, p. 3)

[16] “Waterford students dig history” (students learned Percy King Road was named for potato farmer Percy King) The Oakland Press (May 15, 2009), https://waterfordmi.gov/1205/Richard-L-King, https://www.theoaklandpress.com/2009/05/15/waterford-students-dig-history/

[17] Fred Arone, a co-author of several books on Ardsley’s history and a founding member of the Ardsley Historical Society, was an avid collector of Native American artifacts. His superb collection of arrowheads is on display in Greenburgh’s Town Hall. Similarly, renowned Ardsley folk artist Anthony Radomski’s works often featured Native American themes. One of his works depicting Native American motifs is on display at the Ardsley Middle School, the site of an unsuccessful effort in the late 1960s to preserve a 450-year old Native American “Pow Wow” tree. Ardsley's Pow Wow Council Tree

[19] Dr. Lorthrop further related that “based on its overall unrefined form, the “Ardsley” birdstone is unfinished (thus technically, a "preform"), where the overall shape has been roughed out but not refined and finished.” At an auction, these prehistoric artifacts sell for hundreds of thousands of dollars.

[20] Tewanima’s first name was sometimes spelled Louis. However, his birth name was Tsökahovi.

[21] The New York Times, November 5, 2017. The First Marathon In 1911, Tewanima won the modified New York City Marathon (a 12-mile race from Fordham in the Bronx to City Hall in Manhattan) estimated to be witnessed by one million people. A Look Back at the 1911 Running Scene (New York Times, October 31, 2008)

[22] November 13, 1908, p. 7. Yonkers is named after Dutch landowner Adriaen van der Donck.

[23] http://www.nativepartnership.org/site/PageServer?pagename=airc_hist_boardingschools

[24] The Indian Craftsman, Vol 1, No. 3 An article in this issue entitled “Tewanima, the Great Hopi Runner and Marathon Winner” detailed his numerous racing victories and contained a picture of Tewanima and his many medals and trophies.

[25] The Assimilation, Removal, and Elimination of Native Americans In recognition of the thousands of Native Americans who had served in the American armed forces during World War 1, “progressive” Senators pressed for the granting of American citizenship to Native Americans, The Indian Citizenship Act of 1924 (“ICA”) was signed into law by President Calvin Coolidge on June 2nd. AN ACT To authorize the Secretary of the Interior to issue certificates of citizenship to Indians. The law’s chief sponsor was Republican five-term Representative Homer Peter Snyder (1863-1937) of Amsterdam, New York, which is in the Mohawk Valley. The passage of the ICA led to a decade of reform efforts on behalf of the Native American tribes culminating a decade later in 1934 in the Indian Reorganization Act (known as the “Indian New Deal”) signed by President Franklin Roosevelt, which sought to undo America’s long-standing cultural assimilation policies toward Native Americans, the trauma of which many Native Americans still experience. World War 1 marked the first time speakers of various Native American languages were employed by the US Military as “code talkers,” Native American armed service members who used their little-known native languages to convey secret communications. Notwithstanding the American citizenship granted to Native Americans under the ICA, the right to vote was still controlled by state law.Utah was the last state to fully guarantee voting rights to Native Americans in 1962.

[26] Recent scholarship on Indian Boarding Schools has been highly critical. See, A Lethal Education: Institutionalized Negligence, Epidemiology, and Death in Native American Boarding Schools, 1879-1934

[27] November 17, 1908, p. 7

[28] The American Marathon (Syracuse University Press, 1998), p. 10 (accessible on the internet archive) (archive.org)

[29] The 1908 Olympics were originally scheduled to be held in Rome, but the eruption of Mt. Vesuvius required their relocation to London. The American team traveled to London by steamship. The 1908 Marathon controversially ended with American Johnny Hayes being declared the winner when the Italian finisher (Dorando) was disqualified due to receiving assistance during the last few yards of the race. Marathoners like Hayes and Crowley belonged to Irish-American running clubs that dominated American marathoners' early years. Notably, “Irish-American Athletic Club’s only criteria were athletic prowess and pluck. It didn’t restrict membership by race or ethnicity, instead welcoming blacks, Jews, Italians, Hispanics, and others who were excluded from high-toned outfits like the New York Athletic Club.” When “Bricklayer Bill” Won the 1917 Boston Marathon, It Was a Victory For All Irish Americans No American would win the Olympic Marathon until Frank Shorter's victory in 1972. Rome hosted the Olympics in 1960, where African American competitor Wilma Rudolph, a former polio patient, won three gold medals in sprint events, and Abele Bikila of Ethiopia won the marathon while running barefooted to become the first black African Olympic champion.

[31] Several Ardsley roads, such as Concord and Revere roads, pay homage to its colonial history incuding Colonial Road that bisects the Ardsley Green shopping in downtown Ardsley. In addition, three streets are named for Presidents (Taft, Lincoln, and McKinley). None recall its Native American heritage other than perhaps Tappan Terrace, a cul-de-sac off Victoria Road which is adjacent to Franklin Court also off Victoria. Cohawaney Road in Scarsdale (near the Bronx River Parkway) is named for a member of the Weckquaeskeck who signed a treaty with Caleb Heathcoate, New York City’s 31st Mayor whose ancestral home in England gave Scarsdale its name. https://www.scarsdalehistoricalsociety.org/streets-place-names